The rover fireflies ( Photinus) are a genus of the Lampyridae family of beetle. Image Denis Doucet

The rover fireflies ( Photinus) are a genus of the Lampyridae family of beetle. Image Denis Doucet Jenn Shelby’s lovely article on fireflies accompanied by Denis Doucet’s photo (at left) sent me out into our yard in search of the little creatures to show my grandson. I found one in daylight, but once deposited in a jar, it failed to flash when darkness fell.

Denis advises that of New Brunswick’s dozen species, only eight or nine produce light.

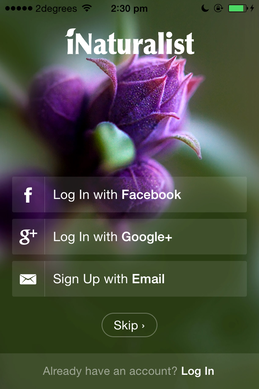

The next day, I realized my firefly was subtly different than Denis’s photo. So, I photographed it and uploaded it to iNaturalist.ca to see which species it was. Pyractomena borealis, I soon discovered. A map of observations showed its range to be from the Mexican border all the way up the east coast to New Brunswick and then west to the Great Lakes.

The dreaded spotted spurge. Image Deborah Carr

The dreaded spotted spurge. Image Deborah Carr Spying an alder bush riddled with sapphire-coloured bugs, I snapped a photo with my cellphone and uploaded it to the iNat app on my smartphone.

The app records the date and GPS location, then compares the photo to its database, responding with a list of suggestions that helped me identify it as the Alder Flea Beetle. I was then able to find out more about the insect.

I also identified a low-growing plant that was colonizing on my garden path as the invasive spotted spurge, and was thus able to discover how to eliminate it before it invades my lawn.

iNat places a global network of scientists and naturalists in the palm of my hand. Within seconds, I’m able to access an extensive database of information, and the app does the work of narrowing down the possibilities.

Initially, an observation is classified as ‘casual’, but once verified by two experts it’s re-classified as ‘research grade’ and the record may be used by important databases like the Global Biodiversity Information (GBI) system. Typically, the GBI has depended upon museum specimens to track global biodiversity and population trends, but now iNat’s research grade data is informing scientists and researchers throughout the world.

This is, by far, the coolest part of the program. What’s not to love?

The iNat app is available for Android or Apple phones.

The iNat app is available for Android or Apple phones. “Because of these citizen-scientist observations, we’re seeing reports of species not previously found within the region,” says James Pagé, Species at Risk and Biodiversity Specialist with Canadian Wildlife Federation. “So, we can ask, did they actually move north, or is it climate change, or just because people are now reporting them?”

James helped create the Canadian version of the original iNat application, working with Parks Canada, the Royal Ontario Museum and NatureServe Canada to create a database catered to Canada’s northern species.

Thanks to smartphones and apps, science is no longer just within the purview of academics or the trained elite. Citizen observations are important because they often occur outside areas normally covered by the scientific community. “No matter how good they are, your experts can’t be everywhere,” James points out. “But with all their outdoor activities, citizen scientists can cover a lot more ground.”

Citizen scientists are particularly valuable in less populated areas, where habitats are harder to reach and conducting research is cost-prohibitive. Now hikers and backpackers traveling in back-country locations might provide important observations that can help inform decisions on everything from policy to property management plans.

Twelve-spotted skimmer. Image Deborah Carr

Twelve-spotted skimmer. Image Deborah Carr “This opens up a whole world of discovery,” says Dan Kraus, NCC’s national conservation scientist. “You can easily see where no one has entered iNat records, then fill in that little blank spot in our nature knowledge. When you have thousands doing that, you have this incredible amount of new information that can be used in new ways to protect nature.”

As citizens are recording their observations on iNat, researchers around the world are accessing the verified data, and discovering new ranges, trends and population status, including data for species at risk. Over 20 different publications in peer-reviewed journals now contain data from iNat.

“The great thing about this technology is that anyone who wants to contribute to nature and conservation can do so in a meaningful way,” says Dan. “This provides us with new insights on how species are distributed, how they’re using the landscape, and most importantly from our perspective, what their conservation needs may be.”

This way, technology supports learning by helping people identify species more quickly, no matter whether they are on home ground or traveling. Birders and naturalists also cite the convenience of the app in that they no longer need to travel with bulky field guides and notebooks. Their recorded sightings are also accessible to birding peers and scientists. iNat even has a version for children, which doesn’t require personal information.

“Those who work in conservation are often concerned that technology will distance us from nature,” says Dan. “But these apps create opportunities for us to connect with nature in a way we haven’t been able to before. When we can participate in information-sharing that has meaningful outcomes in conservation, that’s pretty cool.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed