Fundy Park biologists inventorying salmon at Black Hole. Image Deborah Carr

Fundy Park biologists inventorying salmon at Black Hole. Image Deborah Carr In late spring of 2018, deep in the backcountry of Fundy National Park, a group of Resource Management Officers made a fishy discovery in a pile of animal scat (fecal matter). Their day started just like any other, a quick morning meeting before grabbing a radio, hopping in the truck and heading out in the field. The crew was deploying temperature loggers in streams, which continuously monitor the water quality and help ensure the ecological integrity of Fundy National Park.

Passive Integrated Transponders – through the looking glass

This small glass capsule- approximately 2cm in length- caught the eye of the Resource Conservation team as they were walking by because PIT tags are used in the Fundy National Park Conservation and Restoration program called Fundy Salmon Recovery. Each spring and fall the Fundy Resource Conservation team, and its partners in FSR, insert tags in wild salmon smolt and adult salmon. Biologists do this so they can follow the family history of the salmon, as well as track them as they mature to know when they return to their native rivers in Fundy National Park to spawn.

Neil Vinson, Resource Management Officer for Fundy National Park, did not hesitate to collect this capsule from the scat. This tag would act as a looking glass into the life of this endangered, wild Inner Bay of Fundy Atlantic salmon.

“Of course we had to take it with us,” says Vinson. “We weren’t out looking for salmon that day, so we didn’t have the proper equipment with us to scan the PIT tag to investigate. Also, we wanted to know which kind of scat this was, but it was hard to tell since it looked fairly weathered.”

Once the tag was back at the office, a quick scan with the PIT tag reader revealed this fish’s ID number, along with some information about his life. To identify the culprit, a photo of the scat was sent to partners at the Maritime College of Forest Technology, who confirmed that it was indeed a coyote.

Eulogy of Salmon #515176

This particular salmon was first released to Fundy National Park waters as a fry in the spring of 2013. After growing in the wild for a year and a half, he was collected as a parr in the fall of 2014 and brought to a hatchery run by Fisheries and Oceans Canada outside of Fredericton, NB. By the spring of 2015, he was ready to be moved from freshwater to saltwater. He was later transported as a smolt to the World’s First Wild Atlantic Salmon Marine Conservation Farm on Grand Manan Island, NB, where Cooke Aquaculture and the Atlantic Canada Fish Farmers Association grow wild Fundy Salmon Recovery smolts to maturity.

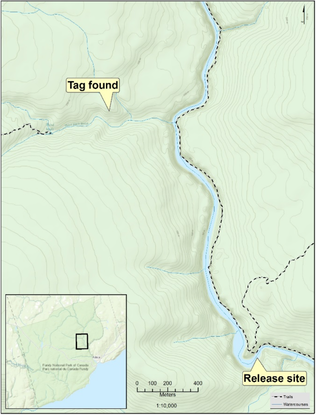

In September 2017, this wild exposed salmon measured in at 67.5 cm long and weighed a healthy 3.67 kg – he was ready to return to the wild. On release day, October 12th 2017, this salmon was delivered by helicopter to Black Hole pool on the Upper Salmon River in Fundy National Park.

After this fish was released back to the wild, the details of its life become less clear. The PIT tag was found approximately 3 km upstream from the release site at Black Hole pool, and about 1 km into the woods west of the river. Did the fish make his way that far upstream looking for a suitable female to spawn with, or did our salmon snacker take this prey to a quiet place to eat in private? How long did this salmon live in the river and was he able to spawn before he met his demise?

A needle in a haystack

The discovery of this PIT tag offered a fascinating opportunity to follow the life of a wild iBoF Atlantic salmon, and speculate at some of the missing details that we may never know.

“It’s amazing to think that I was part of the river crew that released this exact fish at Black Hole last fall, and seven months later we just happened upon this pile of scat and noticed part of the tag showing,” recalls Vinson. “Fundy National Park is over 200 km2. It really does feel like we found a needle in a haystack.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed