The maps caught my attention as soon as I walked in the room at a recent Sea Level Rise workshop. The colourful depictions of predicted high water zones for the year 2100 were spread out over three tables. I looked more closely. The Alma Wharf, Parkland Village Inn and Alma Lobster Shop were in flood zones. So were Water Street and the crossroads at 915/114 in Riverside-Albert. The Railway Diner and Golf Club Road in Hillsborough. Grey’s Island will be an island, again. These were just some of the vulnerable areas identified in the three villages.

Highwater zones in Hillsborough are identified in red. (click to enlarge)

Highwater zones in Hillsborough are identified in red. (click to enlarge) Certainly, we’ve all been made aware of significant climate changes over the past decade and predicted changes for NB paint a grim picture: increased storms and intensity, flooding, changing river levels, droughts. Last month’s flooding along the Saint John River Valley shows clearly how devastating and costly rising water can be.

Despite the fact that scientists have been warning us since the 80s, terms like Global Warming, Climate Change and Sea Level Rise have only recently been elevated in the media. Global warming is the most critical issue of our time. Whether or not the planet remains habitable for human life is in our hands.

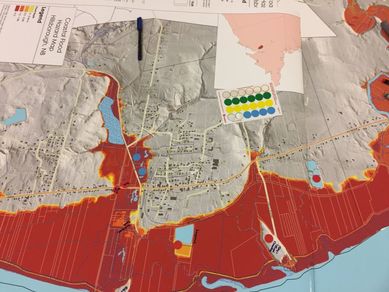

Flood zones in Riverside-Albert identified by light blue. Participants were asked to paste circles on the map to identify landmarks. (click to enlarge)

Flood zones in Riverside-Albert identified by light blue. Participants were asked to paste circles on the map to identify landmarks. (click to enlarge) Sure, we’re looking ahead 80 years. It may be easy to say, ‘I’ll be gone, so I don’t care,’ but we have a responsibility to help fix what we’ve broken for future generations and the effects are being felt already. Human beings are causing climate change, largely by burning fossil fuels. Will this be our legacy to our grandchildren and great-grandchildren?

One participant pointed out that New Brunswick simply cannot afford the costs associated with climate adaptation. Our only option is to work harder at reducing the use of fossil fuels, and hope we can attain a ‘less-than-worst-case’ scenario. Fixing this isn’t as hard as one would imagine. We currently have the technology to make significant changes, but so far, the political will to lead is weak and inadequate. This will only improve with public pressure.

Since the coal-burning era of 1850 onward, greenhouse gas emissions have increased 150%. We’ve a responsibility to the future generations to adjust our lifestyles, decrease our consumptive habits, and to push our political leaders to take more concrete and decisive steps towards reducing GHG emissions, and to provide us with better, cleaner energy choices.

The Village of Alma flood zones shown in brown. (click to enlarge)

The Village of Alma flood zones shown in brown. (click to enlarge) Greenhouse gases contribute to a warmer climate, which speeds up the melting of glaciers and ice caps. As oceans continue increasing in volume through this meltwater, they are also absorbing 90% of the heat generated by global warming. And warm water takes up more space than cold water.

Previous 2012 calculations anticipated a rise of 0.85 metre (2.75 feet), but the latest prediction is that the global sea level will be one metre (3.25 feet) higher than current levels by 2100; two metres (6.5 feet) along the Bay of Fundy.

And if our ‘worst case’ keeps steadily increasing, we may see greater changes, sooner. (See this recent article on ice melt in Antarctica.)

The Bay of Fundy tides are also amplifying. In his 2014 report on sea level rise predictions for New Brunswick, meteorologist Réal Daigle predicts a 30cm (1 foot) increase in the Fundy tides, in addition to global sea rise.

Predictions are complicated because the melting ice cap also removes immense pressure from the Earth’s crust and the crust rebounds (rises), which causes subsidence (sinking) in other areas. Think of lifting a crust of floating ice. As you slip your fingers underneath and lift one end, the opposite end sinks. So, as the land rebounds further north, here on the Bay of Fundy, and at points south, coastal land subsides.

It's important for communities to be aware of what lies ahead, and for people to begin having conversations about climate change. Keeping a worst case scenario in mind is important for all future coastal developments. From a community planning perspective, there are several ways to reduce the risk and prepare for rising seas:

- Protect: Creating natural or man-made infrastructure to help maintain the shorelines and prevent erosion. Such as the new seawall in Alma. As one participant pointed out, trees prevent erosion too, so it’s important to preserve forests, particularly along coastal areas.

- Accommodate: Manage the way we use coastal areas to minimize the risk to humans and infrastructure. And maintaining wetlands and marshes as they are important buffer zones.

- Retreat: Relocating existing structures further inland away from flood zones.

- Avoid: Preventing new developments in low lying areas, areas vulnerable to erosion, and flood risk zones.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed