In the early 1960s, I was moved from New Brunswick to a cabin on the Whitefish River exactly where “Rainbow Country” was filmed later in the decade. This had once been an Indian Reservation until the pure silica discovered in the adjoining La Cloche Mountains was needed in a Sudbury smelter. Regardless, the Ojibwa, who were there at least since the Huron extermination, weren’t going anywhere.

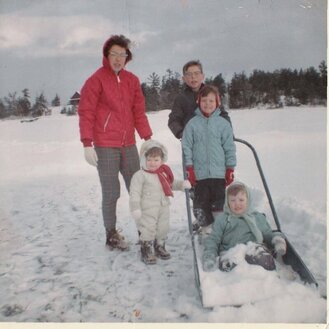

(Photo caption: Brownie snapshot by the late Robert Kitts of his then family, maybe 1964, late wife Alice (Fullerton), daughters Colleen, Cindy, Wendy and son Jim, just beginning to clear ice prior to ice cutting operations. Alice is the author of Emily of the Bend, an English/French picture book recently re-released by the family and the Steeves House Museum. The family sponsors the Alice Kitts Memorial Award for excellence in Children's writing in her memory. )

When the black-robed nuns let me out of the hospital, we had moved way up the North Channel between Manitoulin Island and the mainland. I started school by correspondence just as the ice was locking us into our island cabin. The idea was to get all your school books, pencils and such in the mail while you could still get to the Post Office by boat before the ice stranded you. You did as much as possible while the light wasgood before the small powerline from the mainland went down for the winter. After that, it was kerosene lamps and hard-going, even with young eyes. If you kept at it, you could finish school by the end of April, while constantly contending with the ever-present ice.

Every morning, I went to the lake with two pails. I chopped and bailed away ice at the “ice hole,” which built up into a volcano shape as the winter progressed. Hauling water and wood was routine, just a break in the fresh air that you didn’t think about, except after dark when the flashlight reflected strange eyes seeming to go on and off as heads turned to and away from you. But no problem. What lived in our neighbourhood knew we ate local and had good reason to be gun-shy of me.

The other duty was hard, cold and bothersome. I needed to keep a big skating rink shovelled so the ice off our docks would freeze as deeply as possible. It was more than three feet thick in the winters out there in our little pocket of Lake Huron. I had never seen ice cut before. This was a big operation scaled to deal with the refrigeration needs of the large multi-cabin summer fishing resort we were stationed on.

In those days, children were there to be “seen but not heard,” so when the team of horses came jingling across the hard windswept ice, I had no idea what would happen. The big sleigh behind the horses was loaded tall with hay. The “gang,” most of whom were walking, were our fishing guides coming to make very little money and eat as much as possible. It was a joyous event; Ojibwa are always like that. You don’t notice their “way” until you work with someone else. The horses settled under some sheltering pine trees while the men settled into the bunkhouse to play cards.

Next morning, after a mammoth bacon and egg breakfast, the gang split up. One group began the wet and freezing job of physically busting down through...I’m going to say...three feet of ice (above the height of my elbows but below the shoulders). They used axes and large sharpened heavy iron bars about a man’s height. Once they cut down to the water, they chopped a ramp into the ice to get the blocks out and switched to wooden-handled ice chisels because the iron bars froze over and got too slippery to use. Water flooded up on the ice and men danced and slid around more than walked.

Meanwhile the more experienced men set off the first cut line leading from the ramp. This line would control the whole job and determine the team’s movements up to and away from the ramp. A straight line was scratched in the ice. That line was followed by a home-fabricated, gas-powered cutting sledge that looked and operated like a big round saw blade attached to one end of a teeter-totter. At each blade-down motion, ice chips flew skyward in a rooster tail plume dusting everybody crystal white. During the blade-up motion, the “hit-n-miss” engine picked up speed and the sledge was yanked backwards along the scratch line to continue the cut. Parallel lines two feet apart were scratched into the ice to mark the width of the block rows, then right angle lines were set off every four feet to mark the block ends.

All the chainsaws on the Reserve started up. Everybody attacked the block lines on the first row down to the depth of the chainsaw bars filling the scene with two-stroke smoke. The team followed swiftly behind using T-handled ice saws that were as tall as the men. When the smoke cleared, all the saws were shut off and thrown aside and the teeter-totter yanked out of the way.

The team of horses came down crunching their way onto the wet ice enjoying the traction of heavily-caulked shoes suitable for this work. It took a bit to coax them to back up the sledge near the ramp.

The gang chipped into the shallow saw cuts with long, wooden-handled ice chisels wedging off the blocks closest to the ramp, then set them to float. Two men started tonging whole blocks up the ramp to park on the ice surface. Without words in any language (Ojibwa was the working language), a second group formed, our three best men, who downed a bit of whiskey and tonged and manhandled the wet blocks up a ramp onto the sleigh. The team finally made a first run for the ice house.

This was my signal to grab on and ride. Upon arrival, I joined up with “Old Deaf Mike,” an ancient Ojibwa who specialized in packing ice houses. As the ice blocks came skidding in on tongs, he just pointed to show which blocks were keepers and which were discards to be used in packing. No one ever argued. He didn’t have to pretend he couldn’t hear.

Approved blocks were slid up hard to their neighbours. My job was to smash the discards into pieces to be jammed into anywhere we found a space. Then sawdust was tramped into any void that was left. We built three tiers of ice topped with about two feet of sawdust in a building the size of a barn.

The whole ice operation with horses and the gang required about a week in good weather, all the groceries you could find, significant medicinal libation and enough influence to pull the team away from other ice jobs.

If you did it right, there was enough ice in there for a “solid” year. If I knew better at the time, I would have said “that’s cool.” And it was.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed